Drinking sake is a lot of fun, school is not. To enter the world of sake, however, you have to learn a little math, a little science, a little vocabulary, and a dash of history. Sake is delicious, but it requires a baseline level of knowledge to figure out what you’re going to like.

Sake 101

Like wine, sake’s story is a mixture of history and science, and you can approach it from wherever you want to start. If you want to nerd out about fermentation, you can do that with sake. If you want to learn about Japanese history, you can also go that way. There’s an endless amount of access points for it, but we’re going to give you a brief overview of how it’s made, what tasting notes to look for, and why it’s so good. School is in session, so take your seat…

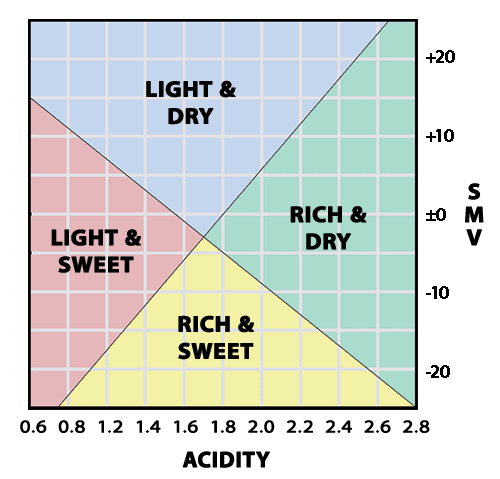

Sake Meter Values & Acidity

There won’t be a lot of math. We promise. You’ll just have to read a graph and remember how x and y axes work. The flavor profile of sake has a special system of measurement—SMV (Sake Meter Value) and then acidity. The graph of these two things gives you the character of what you’re drinking. Will it be dry? Sweet? Light? Heavy? A negative SMV will give you a sweeter character, while a positive one will give you a drier sake.

“Nigori, which you’ll find a lot in the domestic market, starts at -10,” beverage director and Skurnik Wines importer Alyssa McGrath explained. This makes it ideal for the end of a meal, since it’s sweeter, like a dessert wine is.

How Do You Make Sake?

As with other types of liquor, producers have to make choices along the way that have far-reaching consequences for what goes into the bottle in the end. Beyond the acidity and SMV scale, the other things that give sake its character are polishing, koji, and whether or not the brewer decides to add in distillate, which is extra alcohol. Adding distillate changes the flavor and consistency of the final brew.

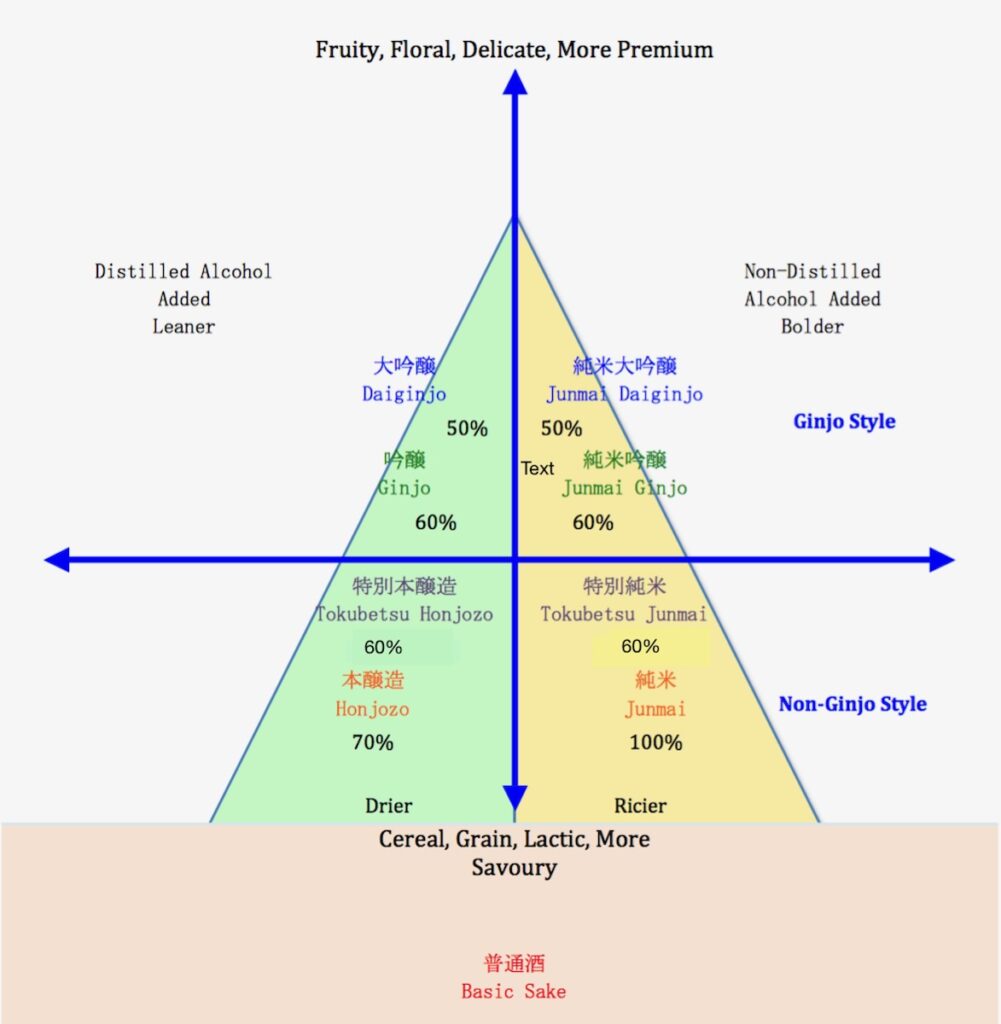

Polishing is the process by which producers mill the rice to get rid of the outer layers. Typically, the higher the polishing rate, the smoother and more delicate the product is. House of Sake produced a diagram to illustrate this concept.

The percentages refer to minimum rice polishing. The higher up it is on the diagram, the more premium, but the number is lower because it refers to the ratio of un-polished rice to polished rice. So, if you’re looking to impress with sake, you want to look for the lower number, since the lower it is, the more ground-down the rice is. A 50% polishing percentage means the rice is now 50% of its original size.

Along with the math, allow me to break down a brief vocabulary lesson to guide looking at the terms in the triangle:

- Junmai means “pure rice.” This indicated that the producer didn’t add any distillate into the sake.

- Honjozo will have a bit of distillate added in—so you get a higher alcohol percentage and a leaner body.

- Ginjo also has an addition of a distillate, but its polishing is more refined than Honjozo, hence why they are not the same thing. As you go up the pyramid, you see the Tokubetsu (meaning “special”) and Dai (meaning “big”) prefixes to show what’s considered more refined.

- There is a sub-style, Junmai Ginjo, that is also a higher polishing level than your typical Junmai but doesn’t have that distillate in it.

Each of the terms tell you how polished the rice is and whether it has distillate. So, looking at all the information nested in the vocabulary words, Junmai Daiginjo is a highly polished, no-distillate sake. Daiginjo is a highly polished sake that does have distillate. Tokubetsu Honjozo will be a 60% polishing percentage with the addition of distillate.

Koji: A Little Mold Goes a Long Way

Koji is a mold, but it’s not the type of mold you’re thinking. It’s what makes sake alcoholic. Normally, the idea of ingesting mold is unappealing. But in this case, koji-kin, a small, harmless to eat mold, is cultivated onto the rice during the sake-making process. All drinks that come from starches require something to break down the starch into sugars, which the yeast in the starch will eat to create alcohol. However, you can’t “malt” rice the way you can with barley. So, something else has to happen in order to create alcohol.

That’s where koji comes in. Producers grow koji is a separate part of the brewery called a koji muro and then sprinkle it onto steamed rice. The koji is in an integral part of the sake-making process and it influences the quality and flavor of the final beverage. Even the material on the walls of the koji muro can make their way into the final beverage’s flavor profile. At the higher end, there’s one more categorization: namazake or unpasteurized sake, which brewers don’t add heat to. That’s the purest form of sake, with the freshest expression of the koji in it.

The History of Sake

Ok, maybe you’re sick of looking at graphs and talking about mold now. What about the history? “Traditions of sake go back hundreds of years. There’s a big focus on the cleanliness and the pristine nature of the water. The water is part of what gives sake its regional character,” McGrath said. The technique of making sake originally came from China but gained prominence in Japan. (There are many such historical and cultural crossovers between Japan and its neighbor, such as the kanji writing system). The first recorded mention of sake in Japan is in the third century, and the first mention of commercial breweries appears in the 1400s.

Prior to that, nobles in the imperial court and monks were the only people producing sake. The imperial court even had its own sake maker in-house. The court only drank the clearest, purest sake in what we would now consider the Junmai Daiginjo style.

Sake’s first introduction to the global economy was in 1852, during the Meiji period when Japan opened its borders and entered the international trade market. Sake has taken off from there, and there are now sake producers all over the world. It’s become as prestigious as wine and whiskey, with a separate WSET certification to focus on it.

What is it Like to Drink Sake?

Yeah, yeah, history is cool, science is interesting…but beverages are for drinking. As the graphs earlier showed, sake can be drier or sweeter. Often, you’ll find tasting notes referring to more umami (think mushroom-like savory fullness) or more floral or fruit notes depending on the koji, polishing percentage, and regionality.

Different regions of Japan produce different profiles. Kobe, famous for their beef, also produces a lot of sake. The Kobe style tends to have a fuller-body to stand up to the juicy meats. Sake from Hokkaido, by contrast, will pair well with fish, because seafood is a huge part of that region’s cuisine.

When you see “cloudy” sake, that means it’s Nigori, the sweeter style that has some sediment left over from the brewing process. Nigori sake was actually once banned in Japan, during the Meiji period when the country wanted to modernize. The Japanese government thought the clear style looked classier, so Nigori was out. But now, Nigori is one of the most popular kinds of sake for its sweet taste and relative accessibility.

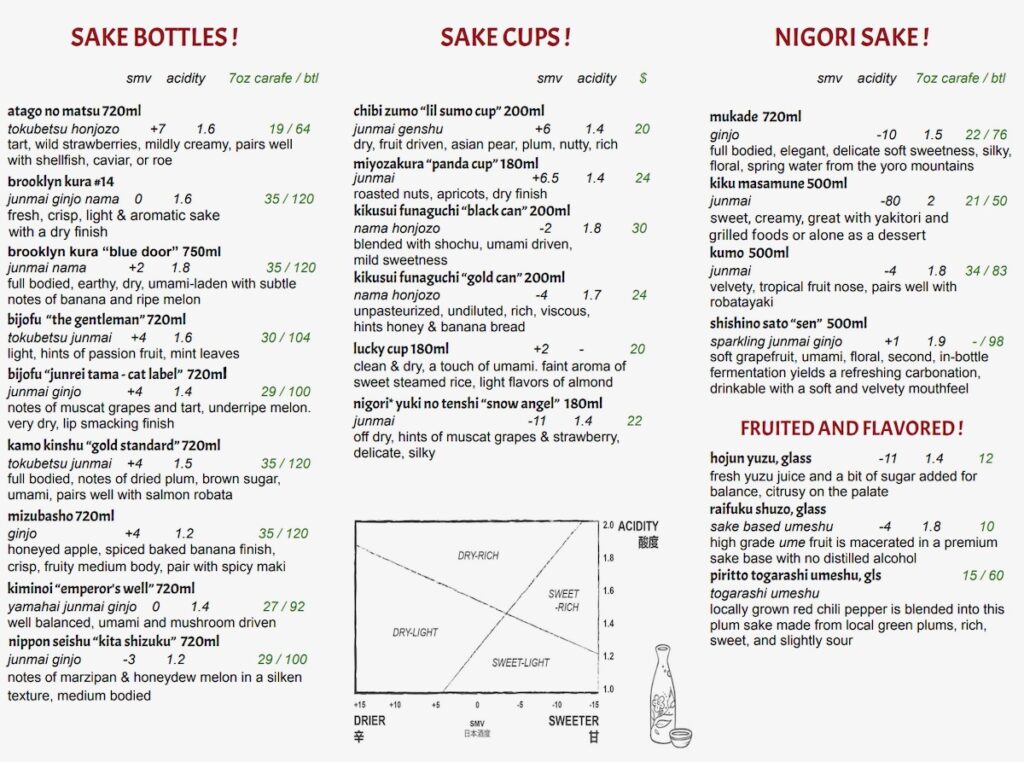

An example menu from Roger Li’s Umami can help you put your knowledge to the test. See if you can recognize the terms and what each one means!

A great way to experience sake’s diversity in practice is a sake flight, which most Asian restaurants (including Umami) offer. The differences are dramatic between different cups of sake. McGrath also encourages people to serve sake with non-Japanese food. Often, because the language seems unfamiliar, people don’t make an effort to learn about it. But sake is as versatile as any other liquor. After all of those numbers, I definitely want a carafe of sake. School’s out.

For more, check out the rest of our liquor education series:

- Get to Know Japanese Whisky

- Vodka Isn’t Just for Shots and Soda

- The Best Bottles of Tequila Blanco

- All About Gin

- The Digestivo Digest

- Vermouth is the Apéritif You Need Right Now

Wondering what to cook to go with your drink? Try our food education series:

- Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Olive Oil

- Knowing Spices Can Completely Change Your Kitchen Game

- Creative Uses For Your Herbs

- How to Use Salt Correctly in Cooking

Photo by Bundo Kim

Story by Emma Riva

Subscribe to TABLE Magazine’s print edition.